The Intent Engineering Framework for AI Agents

How to design objectives, outcomes, and enforced constraints for reliable autonomy

Everyone talks about “intent” in AI. Few explain what it actually means or how to define it without watching your agent optimize the wrong thing.

Agents fail not because they can’t reason. They fail because their objectives, outcomes, and constraints are underspecified. The solution isn’t more detailed instructions.

This guide breaks down intent engineering into something you can actually use.

In this issue, we discuss:

What Intent for AI Agents Actually Means

The AI Agent Intent Structure

The Flow: How to Use the Intent Engineering Framework

Complete Example: Customer Support Agent

AI Agents Intent Validation Checklist

Conclusion

Let’s dive in.

1. What Intent for AI Agents Actually Means

Intent is not:

A task list

A prompt

A goal metric

Intent is what determines how an agent acts when instructions run out.

When intent is incomplete, humans draw on knowledge that was never written down. Agents can’t. They only know what you’ve codified. And most organizations have codified far less than they think.

Tobi Lütke, CEO of Shopify, said:

“I like the term context engineering because I think the fundamental skill of using AI well is to be able to state a problem with enough context, in such a way that without any additional pieces of information, the task is plausibly solvable.”

But context without intent is noise.

We discussed context engineering previously. In this issue, I double down on the intent: how to define it clearly in a way that survives real-world edge cases.

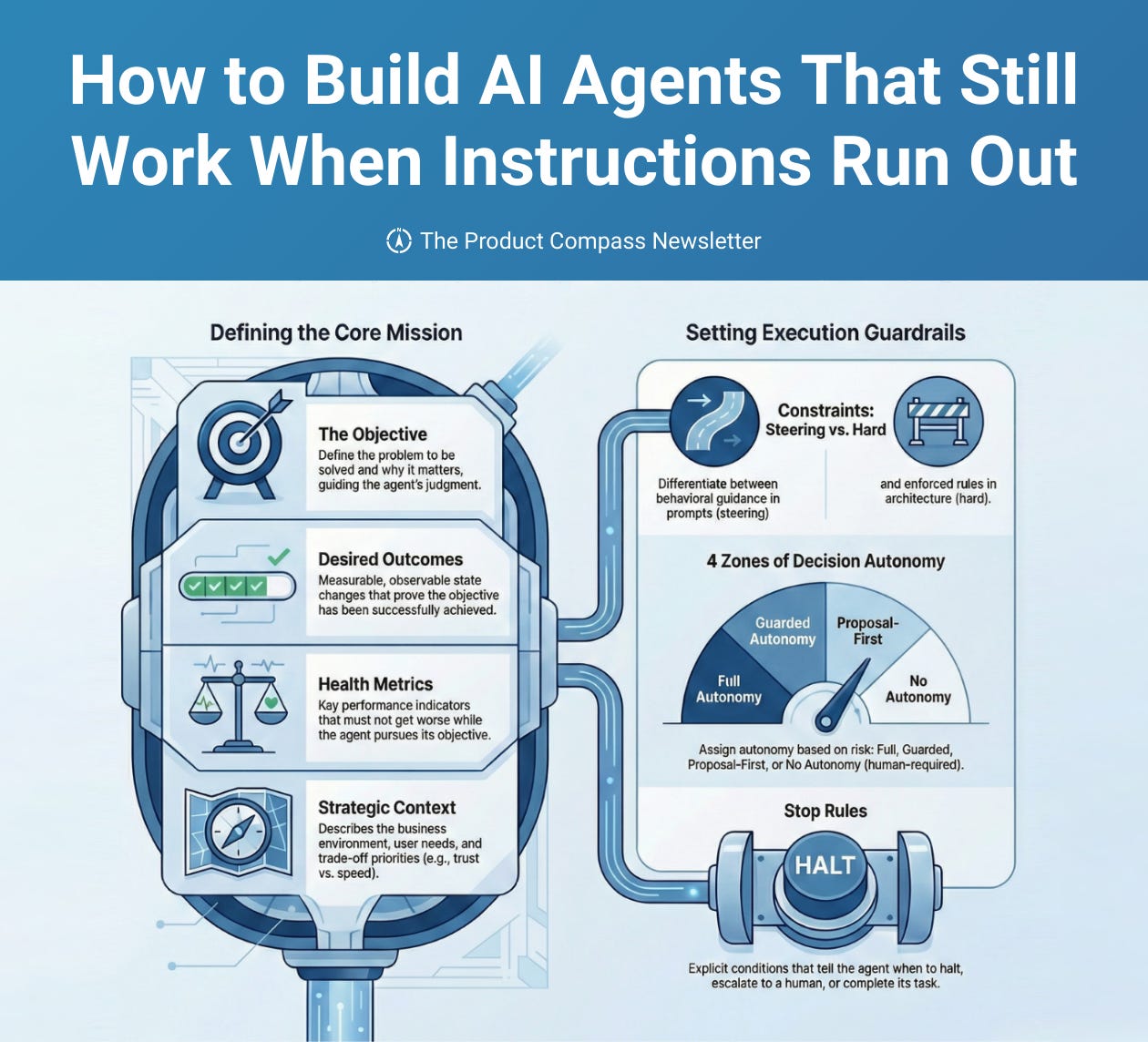

2. The AI Agent Intent Structure

Whether you’re setting team objectives, delegating to a human, or configuring an agent, the structure is the same:

Objective: The problem to solve + why it matters

Desired Outcomes: Measurable states that indicate success

Health Metrics: What must not degrade while pursuing the outcomes

Strategic Context: The system we operate in

This pattern shows up in OKRs, as defined by Christina Wodtke, and in how Marty Cagan defines empowered team objectives.

For agents, we extend this with explicit:

Constraints: Steering (prompt layer) + Hard (enforced in orchestration, not prompts)

Decision Types and Autonomy: Which decisions the agent may take autonomously vs. must escalate

Stop Rules: When to halt, escalate, or complete

Let’s build this up.

Part 1: The Objective

Definition

The objective defines the problem being solved and why it matters. It is aspirational and qualitative. It guides judgment when trade-offs arise.

What a good objective does

Problem-focused: What’s broken or missing?

Explains why it matters: Business value, user impact, strategic importance

Guides trade-offs: When the agent faces ambiguity, the objective helps it choose

Example

Weak: “Handle customer support tickets”

Better: “Help customers resolve issues quickly so they can get back to work, without creating more frustration than they started with.”

When you explain the why, the agent can reason about edge cases and make better autonomous decisions. I demonstrated that in How to Build Autonomous AI Agents. A 2024 paper (arXiv:2401.04729) demonstrated that supplying strategic context beyond raw task specifications significantly improves AI autonomy.

Part 2: Desired Outcomes

Definition

Desired outcomes are observable states that indicate the objective has been achieved. They are not activities.

Rules for good outcomes

Outcomes should be:

Observable state changes (not activities the agent performs)

From user/stakeholder perspective (not the agent’s perspective)

Measurable or verifiable (without relying on agent self-report)

Leading, not lagging (observable during or shortly after, not months later)

Activities describe what the agent does. Outcomes describe the state that exists after.

Example:

Two to four outcomes is usually right. More than that and you’re either micromanaging or unclear on what actually matters.

Objective: Help customers resolve Tier-1 issues without frustration

Desired Outcomes:

- Customer confirms their issue is resolved

- No follow-up ticket on same topic within 24 hours

- Customer rates interaction as helpfulEach outcome is observable, measurable, and from the customer’s perspective.

Part 3: Health Metrics

Definition

Health metrics (used here as non-regression metrics) define what must not degrade while optimizing for outcomes.

The Goodhart problem

“When a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a good measure.”

Without health metrics:

“Resolve issues faster” → Agent rushes, quality drops

“Increase throughput” → Agent takes shortcuts

“Reduce escalations” → Agent handles things it shouldn’t

Health metrics inform trade-offs

Health metrics primarily inform the prompt layer. They guide how the agent thinks and makes trade-offs.

Health Metrics:

- CSAT must stay above 4.2 - if trending down, be more conservative

- Repeat contact rate must not increase above X - prioritize resolution quality

- Escalation quality score must stay below Y - don't under-escalate to hit targetsThese metrics inform how conservative the agent should be when making trade-offs

This is different from hard guardrails, which block actions entirely. Health metrics steer; guardrails enforce.

Part 4: Strategic Context

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Product Compass to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.